Fundamental Analysis

It would be really useful to know the short list of fundamental factors that professional Forex traders use when making trading decisions. The problem is that no such list exists, or at least it does not exist for long. The list is constantly changing, depending on whatever factor is uppermost in the mind of the global investing community at any one moment in time.

The reason for this sad state of affairs is that we do not have a single unified, coherent theory of what determines exchange rates. Academic economists have made a complete hash of exchange rate theory and left exchange rate determination to the whims of a market that nearly always disrespects what the ivory-tower crowd is writing about. The disconnect between theory and practice in the Forex market is the widest of all the markets. At least in equities and commodities, we have a clear picture of what drives supply and demand. It is a lot trickier in Forex.

Failed Theory No. 1 — Purchasing Power Parity

We have to start with the “law of one price,” also called purchasing power parity. This concept states that Currency A should trade in equilibrium with Currency B at an exchange rate that balances trade and investment flows. If Currency A suffers from inflation, its goods will become too expensive for buyers in Currency B and exports will fall, resulting in a trade deficit. Eventually, investors and bankers will choose not to fund a rising deficit and Country A will use up its reserves to pay for imports. Eventually, under fixed exchange rates, Country A has to devalue its currency to restore trade competitiveness. This is still the case with most emerging market currencies that are either fixed or in a “managed float.”

Under floating exchange rates, as we have in the major economies today, investors and bankers will continue to fund a rising trade deficit only if they are compensated with extra-high rates of return (interest rates). Extra-high rates of return have the domestic effect in Country A of stifling demand and, thus, inflation. Eventually, a basket of goods in Country A returns to price parity with the identical basket of goods in Country B.

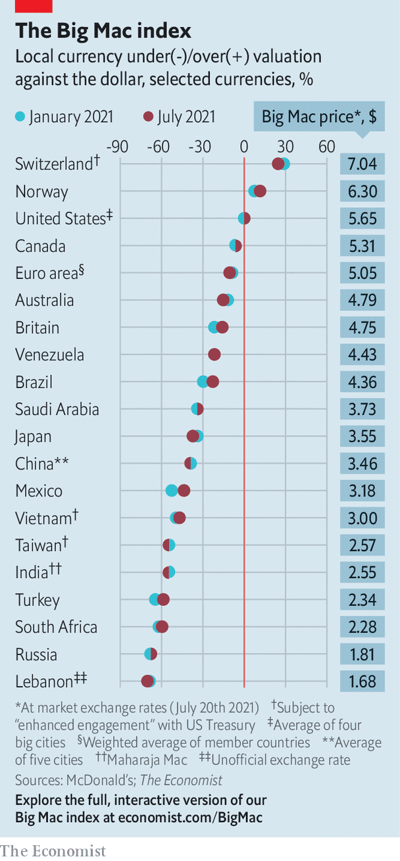

This is named purchasing power parity, a powerful and seemingly logical concept. Every year, The Economist magazine publishes a Big Mac purchasing power comparison that shows what each currency should be worth in dollar terms to equilibrate the cost of a Big Mac in some 80 countries. You can see the under- or overvaluation of every country’s currency against the four majors (dollar, pound, euro, and yen) and also the Chinese yuan.

Here is the idea: if the Big Mac costs more in Country A, the currency is overvalued. If it costs a lot less, it is undervalued. Sometimes — quite often, in fact — the next year we see the overvalued currency having adjusted downward and the undervalued one having adjusted upward. International organizations like the World Bank calculate purchasing power parities, as well as some of the big banks. The European Commission tracks purchasing power in order to track the progress of price convergence, a primary goal.

The basic problem with purchasing power parity is that equilibrium is a fiction invented by economists. It is a state of balance that is never actually achieved, nor is it achievable in the real world. For one thing, every country has a competitive advantage, and that means its costs are permanently lower for some sectors and goods. For example, the USA will always be able to produce grains more cheaply than Japan due to its huge farmlands and economies of scale. The emerging markets of Asia, including China, have sharply lower labor costs in clothing manufacturing, among other items. The equilibration process will take decades, if it is ever possible at all. Champagne can come only from France, and fine-engineered industrial machines are made in Germany. The USA invented the auto industry and produced more cars in 1960 than Germany, but today Germany produces more autos than the USA – with one-quarter the population. You would be hard-pressed to find a correlation between the reversal of fortunes of the USA and German auto industries with the exchange rate since, over this period, the German currency, whether the Deutschmark or the euro, was mostly on an appreciating trajectory. The rise in German exports, according to purchasing power parity, should not be occurring.

Moreover, we are not really sure what to measure. What, exactly, is the typical basket of goods? The basket of goods of the average industrial company or household in Japan is not the same as the basket of goods in the industrial company or household in France, the UK, or the USA. Efforts to make the baskets roughly equivalent are chock-full of factual flaws like differences in quality and are seemingly always out of date. For example, the USA is seeing a resurgence of interest in artisanal and locally produced goods, from hand-milled soap to sustainably produced textiles. The Japanese believe domestically grown rice has properties that Louisiana rice will never have at any price. Relative cost is secondary to these “quality” factors.

Another factor is that services are, on the whole, not tradable across borders. Restaurant meals, haircuts, lawn-mowing, and a host of other services are confined to a single economy. Note that services make up over 75% of the US economy. Whether the dollar appreciates or depreciates against other currencies has no effect on wages or other costs of producing services.

Finally, Japan has run a trade surplus with the US and the rest of the world for over three decades, up until about ten years ago, and yet the Japanese yen has appreciated from nearly 300 to an average of about 100 (as measured by USD/JPY rate) in 1995. A persistent surplus implies the yen has been undervalued, but instead of falling, the yen has been rising. Failure to equilibrate either the trade balance or the currency implies a very big failure of purchasing power parity in the real world.

Do traders heed purchasing power parity? No. It is a curiosity, but we doubt that anyone ever made a trade on the Big Mac index.

In 2021, The Economist explained how undervalued the Vietnamese dong is compared with the US dollar:

Indeed, the Big Mac’s birthplace is one of the priciest places to buy it, according to our comparison of over 70 countries around the world (see chart). In Vietnam, for example, the burger costs 69,000 dong. Although that sounds like an awful lot, you can get a lot of dong for your dollar and, therefore, a lot of bang for your buck in Vietnam. You can buy 69,000 dong for only $3 on the foreign-exchange market. And so a Big Mac in Vietnam works out to be 47% cheaper than in America.

The article pointed out that it is perfectly normal for a poor country to have cheaper goods and services. The problem with that logic is that looking at the comparison chart that shows how various currencies are undervalued/overvalued compared to the dollar, we can see that the Taiwan dollar even more undervalued versus the USD. And that just does not make sense under the PPP theory, considering how thriving the Taiwanese economy is.

Such disparity can be explained by the intentional efforts of Taiwan to devalue its currency, which incurred the wrath of the US government. Yet the Congress also included Vietnam in the list of countries that intentionally devalue their currency. Furthermore, even Switzerland was included in that list, even though, as we can see on the chart, the Swiss franc was not undervalued compared to the US dollar, but on the contrary - overvalued. This suggests that governments (or at the very least the US government) do not pay attention to the purchasing power parity idea, and, probably, you also should not pay it any heed.

Incomplete Theory No. 2 – Relative Interest Rates

Another assumption made by academics that infuriates real-world traders is the idea that interest rates, or the return on money, are “naturally” the same everywhere. If money is more expensive in one country, it is only because international investors foresee a fall in the currency against other currencies that will restore the equilibrium, or so says the theory. In this case, the equilibrium is that principal plus interest in Country A should always equal principal plus interest in Country B. This is named the interest rate parity theory.

The economists’ assumption that the chief purpose of cross-border capital flows is to equilibrate exchange rates is ridiculous on the face of it. In fact, international investors seek higher yields in foreign markets despite knowing that, eventually, those flows may cause a currency to change to their disadvantage. The reason the interest rate parity assumption is wrong is a fatal disregard for relative risk in each market, and risk analysis takes into consideration other factors such as variety and liquidity preference. One reason the USA is a desirable investment destination is not only the size of the economy the and rule of law but also the tremendous size of markets, as well as the variety of types of investment vehicles and their risk profiles.

While investors obviously are not motivated as theorists assert, the fact remains that interest rate parity does work, at least most of the time. If all other things are equal (like growth and inflation rates), an interest rate hike in Country A relative to rates in Country B should cause Currency A to fall, keeping the total rate of return, factoring in the currency value, more or less equal. Historically, we do see long periods of time when the relative interest rate differential is highly correlated with a particular currency pair. Remember the problem with purchasing power parity and the USD/JPY? It is solved when you chart the US/Japan 10-year interest rate differential against the USD/JPY. The correlation is very high. It is also high between the USD/GBP, USD/EUR, and other developed country rate differentials.

It is one of the enduring mysteries of the modern world, overflowing with superfluous information, that nobody publishes interest rate differentials as a standalone data series. You can get interest rates for all maturities for each country, but you have to do the arithmetic yourself.

A refinement of the interest rate parity assumption is that in times of relative calm, markets assume that the 10-year note is the relevant interest rate to look at. In times of turbulence, like the financial crisis of 2007-08, the two-year becomes the most-watched differential.

A Difference in Kind — The Carry-Trade

It is critical to note that what works among peers in developed countries is entirely different in emerging markets. It is more than a difference of scale — it is a difference in kind. Investors who borrow in relatively cheaper developed country money markets in order to invest in relatively higher-yielding emerging markets are carry-traders. They are not buying the emerging market currency for any reason other than to take advantage of its higher rate of return. The higher the rate, the more attractive the currency — within limits. An investor may like the 8% return in, say, Turkey but shun 38% in Nigeria because of Nigeria’s country risk, the risk of fraud, expropriation, accounting errors, and other problems, either real or imagined.

This leads us to the observation that risk appetite operates on a sliding scale. The carry-trader is, by definition, a speculator seeking a return higher than he can get at home and prepared to take extra risk to get it, including the risk of devaluation in the carry-trade investment that will wipe out his extra advantage. The country's inflation rate, unless it's completely out of control, is rarely taken into account by carry traders. In times of relative calm, risk appetite is high and capital flows to emerging markets, funded by lower-cost currencies like the dollar, Swiss franc, and yen.

Ironically, capital flows to emerging markets have the perverse effect of causing their currencies to rise, not fall, as the interest rate parity theory demands. Countries like Brazil complained bitterly when the US Federal Reserve cut interest rates to zero because hot money flows to Brazil were pushing inflation as well as lifting the currency, harming exports. Brazilian Finance Minister Mantega used the term “currency war” at a G20 meeting in 2010. Carry-traders were getting a double benefit, not only the higher yield but also currency appreciation.

The problem with the carry trade is that traders assume that any devaluation will be less than the extra yield they are getting, but in a suddenly turbulent period, as during the 2007-08 financial crisis, in the first quarter of 2014 with the Russia/Ukraine/Crimea situation, or in the first quarter of 2022 after Russia's invasion of Ukraine, risk aversion rears its head and emerging markets see a rapid devaluation as hot money flows out — in the absence of any change in the interest rate differentials. Funding currencies like the Japanese yen can find themselves suddenly appreciating in leaps and bounds as carry trades are unwound and the money is repatriated.

Risk Sentiment

We may accept that the world is divided roughly into developed countries with relatively slow growth and low but stable interest rates, and the emerging market world has higher growth and higher rates of return — and never the twain shall meet. However, sometimes, a developed country can behave like an emerging market if risk sentiment is at an extreme. Let’s take the case of “The Two ECB Rate Cuts.” In November 2011, the ECB cut its benchmark rate, and instead of buying the euro, as the parity theory calls for, traders sold it. The euro fell not because Europe was offering a relatively lower rate of return, which might seem logical, or even that it had become a funding currency for carry trades (although it probably did), but rather because the peripheral sovereign debt problem was still blazing. At that point, yields on peripheral country bonds were vastly higher than US notes or Bunds because investors demanded extra yield in case the eurozone were to break up.

Now consider the case of November 2013, when the ECB cut rates again. By then, the peripheral sovereign debt crisis was mostly over. Ireland was able to return to the private bond market to high demand and lowish coupons. Portugal, Spain, and Italy were issuing paper without a problem and at lower rates than had been available in years. The international press was trumpeting that the peripheral sovereign debt problem was over. This time, when the ECB cut rates, the euro rose.

In the 2011 case, risk sentiment interfered deeply with the interest parity assumption. In the 2013 case, interest parity worked as theory said it should, equilibrating principal plus interest across borders. A more refined and workable interest rate parity theory would incorporate risk sentiment. The economist’s rule “all other things being equal” is fatal in this, as well as other, cases. All other things are hardly ever equal.

Inflation

We started out with inflation in the purchasing power parity case, saying it would drive a currency down. This is because no one, whether a consumer or an investor, wants to hold a diminishing asset. Consumers rush to spend devaluing currencies, worsening the devaluation, and investors exit for higher “real” returns, “real” meaning after inflation.

Now introduce economist Milton Friedman’s monetary theory that asserts “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” Friedman was building on the ideas of Irving Fisher, the University of Chicago economist who said that money supply times the velocity of money (turnover) is equal to GDP times the inflation rate. Bottom line, a rise in money supply that is excessive for an economy results in inflation. For decades after monetarism became widely accepted in the 1960s, financial markets watched inflation as the sole predictor of central bank interest rate decisions. This was cemented during the tenure of Paul Volcker as a chairman of the Fed in 1979 and 1980 when he raised interest rates repeatedly to starve inflation. It worked — Volcker cut the inflation rate back to an acceptable level.

Ever since then, financial analysts have watched inflation rates as the single most powerful indicator of upcoming central bank policy decisions. When inflation is low, central banks are assumed to leave rates alone. If it is rising, they are assumed to be thinking about a rate hike. Today, in 2023, we indeed have the problem of rapidly rising inflation that carries a risk of turning into hyperinflation. The bias of analysts is to expect rate hikes instead of rate cuts.

Other Influences on Central Banks

When the Fed started cutting interest rates during the financial crisis of 2007-08, it was not because inflation was falling. It was because the economy was falling and falling hard and fast into a Great Recession. Lower interest rates were supposed to goose the economy back into first gear from a dead halt. In this instance, it was the failure of some financial institutions and the subsequent collapse of the US housing market that triggered the crisis. In Europe, the central banks lowered rates, at least in part because of the peripheral sovereign debt crisis. Some central bankers would like to see higher rates to dampen speculative excess that may be encouraging bubbles in some asset classes.

Bottom line, inflation may be the key favor in central bank decision-making, but it is not the only factor. In order to divine central bank intentions, Forex traders watch the factors of the moment, whether it is recession-related unemployment, housing prices, financial institution stability and sustainability, sovereign debt capacity, and so on. This is why, at the beginning of this lesson, we said Forex traders follow an ever-changing list of fundamental factors. Trade deficits and interest rates alone do not explain as much as we need to see.

Traders do watch trade balances and inflation rates for a rough, general overview of how a currency should be priced, as a nod to purchasing power parity, but you will not find professional traders seeking out PPP as a key indicator on which to base a trading position. Traders watch inflation more as a clue to future central bank monetary policy since a rise in rates tends to cause a currency to fall as an equilibrating factor. The equilibration works only in some cases and even then, only some of the time, and you will not find easily accessible data on interest rate differentials, even though differentials are the one solid Forex determinant in a sea of data that is only partly relevant.