What Is Forex Trading?

What Is “Forex”?

“Forex” is the abbreviation most used today for “foreign exchange,” meaning the price of one currency in terms of another currency. By definition, all Forex prices refer to the relationship between two currencies, i.e., a pair of currencies.

The term “Forex” is used interchangeably with the term “FX.” Both are used today, and both refer to the same thing - foreign exchange. The term “FX” is mostly used in the US, while “Forex” was more broadly used in the UK until recently. Professional traders in the US at banks and brokers tend to use the term “FX”, while “Forex” is the term used in the retail market, adopted from British usage. Also used is the word “currency,” as in “I trade currencies” or “something happened in the currency market.”

Foreign exchange refers literally to money, or more accurately, to money in two different denominations. The “exchange” part of the term means giving one thing of monetary value in return for a different thing of equivalent value. The word exchange refers to the transaction in which each of the two parties is willing to exchange their respective basket of money for the equivalent amount of money denominated in the second currency. The price at which the two parties are willing to make the exchange is the exchange rate.

The price of one currency in terms of another currency is called a “rate” and not a “price.” Although in practice, the word “price” is often used as a replacement for the word “rate“, it is not technically accurate. Foreign exchange is the only market in which the word rate is used in place of the word price. The reason for this usage is probably due to the word “rate” being used since the Middle Ages to refer to a tariff or tax levy since converting one currency to another entails applying a ratio or a proportion to one currency relative to the other. A common Latin phrase is “pro rata” from “pro rata parte,” meaning “in proportion.” The word “rate” in English comes from the Latin “rata.”

What Is Being Exchanged?

Since foreign exchange refers to two baskets of money, each with its own denomination, a foreign exchange transaction can be as simple as buying a basket of 165 dollars in return for £100 at an airport kiosk. The exchange rate is $1.65 per UK pound sterling.

Why is the exchange rate not £0.6061 per dollar? This is the same exchange rate, just expressed differently (it is the reciprocal, or 1 divided by 1.65). The answer lies in the historical convention of quoting the price of other currencies in terms of what they cost in pounds. The pound sterling was the benchmark currency for centuries until just after World War II, meaning the central currency against which all other currencies were judged and priced.

After World War II, the US dollar was declared the benchmark currency by the Bretton Woods Agreement of the 44 allied countries, and most other currencies were priced in terms of how many units of foreign currency you could get for one dollar.

As a rule, any money not issued by your home government is “foreign.” The natural way to look at foreign exchange is to ask: “How many units of foreign currency can I get for a fixed amount of my home currency?” This is how a tourist or an importer looks at foreign exchange. But because the dollar is currently the benchmark currency against which almost all others are priced, the dollar comes first in the name of many currency pairs, although not all. The first name in a currency pair is generally the important name, and the second is the secondary or less important one.

Putting a name first is to assume that the fixed amount is denominated in that currency and the variable amount will be the other currency. In other words, the first currency is the base, and you are applying a ratio to derive the price of the second currency. When the European Monetary Union decided to quote the euro in the format “Euro/USD” and “Euro/JPY,” etc., it was a deliberate choice to make the euro the more important of the two currencies in every pair.

The rule is that whichever name comes first is the one that is getting stronger on higher numbers and weaker on lower numbers. Suppose the number goes up in the pound, for example, from 1.6000 to 1.6500. In that case, it means the pound is getting stronger, and by definition, the dollar is getting weaker because, in this pair, the full quote should read GBP/USD. It is accurate to express the quote as $1.6000 to $1.6500, meaning the pound used to cost $1.6000, but now it costs $1.6500. Journalists usually apply the convention of putting the dollar sign in front of the price quote, although brokers and analysts tend not to insert the currency symbol.

This is also true of the euro (EUR/USD), so a higher number always means the euro is getting stronger vis-à-vis the dollar. You could say the EUR/USD moved from 1.3200 to 1.3900, meaning it got more expensive in dollar terms. If you are new to Forex, you can place an imaginary currency symbol in front of the first-named currency to get your bearings. Therefore, the price quote now looks like $1.3200 to $1.3900.

The pound, euro, Australian dollar, and New Zealand dollar are the top key currencies in which the dollar does not come first because of historic convention. All other currencies are quoted in terms of dollars, such as USD/CHF = US dollar against the Swiss franc.

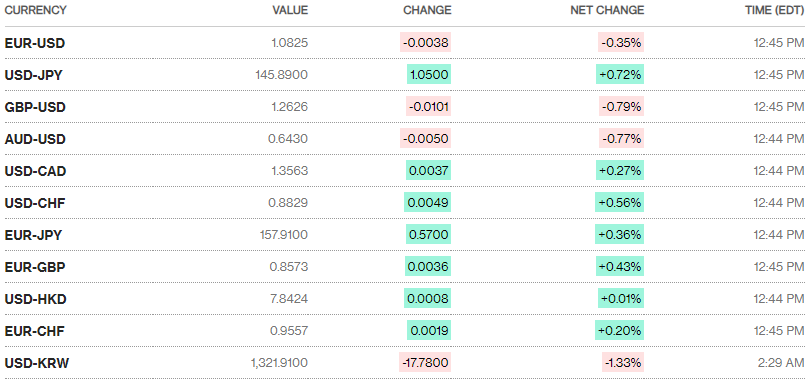

Below is the Bloomberg’s list of major currencies. Bloomberg is one of many market information providers in the professional and retail Forex market. Other providers, including brokers, have their own version of this list.

Cross-rates

A few decades ago, a cross-rate was any currency pair that did not include your home currency. The US dollar/Japanese yen exchange rate would be a cross-rate for someone in the UK or Europe, for example.

Today, however, the common definition of a cross-rate is any currency pair that does not include the dollar. Therefore, the USD/JPY exchange rate is a “major” exchange rate and not seen as a cross-rate by people in the UK or Europe, while the AUD/CAD would be seen as a cross-rate by everyone, including Australians and Canadians, even though the rate includes their home currencies.

This convention for defining a cross-rate is not accepted everywhere, and you will see lists in newspapers and websites that define cross-rates differently. The US dollar accounts for about 60% of global government money reserves, 40% of world trade in goods, and about 90% of global foreign exchange trade, so placing the dollar as a component in all the major exchange rates is not without justification. In fact, there are more dollars in banknotes and bank deposit accounts outside the US than inside the US, so it may be accurate to say the dollar is the most-used currency in some places, even though it is not the home currency. However, when someone says "the euro," he is always talking about EUR/USD and never talking about EUR/GBP, in which case the second currency must be named.

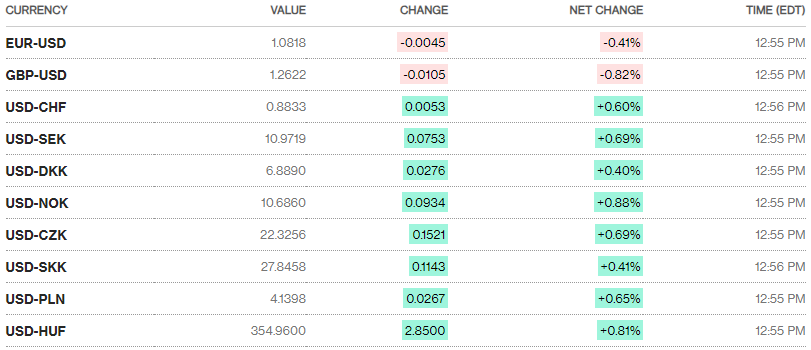

See the list of Bloomberg's European cross-rates. This is a typical list for European countries:

Evolving Practices

Yahoo!, one of the top news and data providers, chooses to include non-dollar crosses as “major world currencies.” As a practical matter, if you are trading euro/dollar, you can say “euro” without the word “dollar”, and you will be understood. If what you really mean is “euro/yen”, though, you must say the name of the second currency.

Trading

When you go to the airport kiosk to exchange your home currency for another one, you are not trading. You are a price-taker. The kiosk sign tells you what exchange rate will be applied, and you are stuck with it. You can take it or leave it.

This is not trading. Trading is the process of going back and forth with the opposing party until you discover the price that makes each of you the least unhappy. Trading involves negotiating a price that satisfies both parties and can involve game-playing, deceit, and other tricks. You may be bidding on something the other person thinks is more valuable than you do, or you may be offering something you value more highly than other people out there who want to buy. When the final price is reached and both parties have agreed upon it, the result is a contract, whether by handshake or formal paperwork, that you will deliver your basket of currency to the other party, and he will deliver his basket of his currency to you at some specified place and time. As a rule, in practice, the actual exchange is a wire transfer from one checking account to another in the two countries of issuance of each currency.

Did you know? Native English speakers never refer to foreign exchange, FX, or Forex as THE Forex. The word “exchange” is a collective noun referring to many transactions. It is a noun created out of a verb and referring to the verb. It does not refer to a building, also named an exchange, where such transactions occur. If you say “I trade the Forex,” you are not using the English language as native speakers use it. It is the equivalent of saying “I went to the swimming”, when the correct usage would be “I went swimming” or “I went to the swimming pool.”

Revealing yourself as not a native English speaker could be to your disadvantage in some situations.

However, it is accurate to say: “I trade Forex on the futures exchange,” since the exchange in this context is literally a real place (even if nearly all of the transactions in FX futures are electronic and not conducted by two persons face-to-face in a specific building). In other words, the word “exchange” is a verb (“to exchange”). It is also a collective noun referring to many acts of exchange, as well as a separate noun referring to a place where the act of exchange may take place. English can be terribly frustrating, but it is important to use each term in the FX industry with precision to avoid misunderstandings and, worse, losses due to language usage errors.

Spanish speakers tend not to make the mistake of inserting the article “the” inappropriately. In Spanish, cambiar is the verb “to exchange”, while el intercambio is the noun for the exchange place or building. One does a cambio de XX por YY, or “conducts an exchange of XX for YY.” This translates perfectly into English.